Active Reading Strategies

Highschool vs. College Reading Expectations

Think back to a high school history or literature class. Those were probably the classes in which you had the most reading. You would be assigned a chapter, or a few pages in a chapter, with the expectation that you would be discussing the reading assignment in class. In class, the teacher would guide you and your classmates through a review of your reading and ask questions to keep the discussion moving. The teacher usually was a key part of how you learned from your reading.

If you have been away from school for some time, it’s likely that your reading has been fairly casual. While time spent with a magazine or newspaper can be important, it’s not the sort of concentrated reading you will do in college. And no one will ask you to write in response to a magazine piece you’ve read or quiz you about a newspaper article.

In college, reading is much different. You will be expected to read much more. For each hour you spend in the classroom, you will be expected to spend two or more additional hours studying between classes, and most of that will be reading. Assignments will be longer (a couple of chapters is common, compared with perhaps only a few pages in high school) and much more difficult. College textbook authors write using many technical terms and include complex ideas. Many college authors include research, and some textbooks are written in a style you may find very dry. You will also have to read from a variety of sources: your textbook, ancillary materials, primary sources, academic journals, periodicals, and online postings. Your assignments in literature courses will be complete books, possibly with convoluted plots and unusual wording or dialects, and they may have so many characters you’ll feel like you need a scorecard to keep them straight.

In college, most instructors do not spend much time reviewing the reading assignment in class. Rather, they expect that you have done the assignment before coming to class and understand the material. The class lecture or discussion is often based on that expectation. Tests, too, are based on that expectation. This is why active reading is so important—it’s up to you to do the reading and comprehend what you read.

Types Of College Reading Materials

As a college student, you will eventually choose a major or focus of study. In your first year or so, though, you’ll probably have to complete “core” or required classes in different subjects. For example, even if you plan to major in English, you may still have to take at least one science, history, and math class. These different academic disciplines (and the instructors who teach them) can vary greatly in terms of the materials that students are assigned to read. Not all college reading is the same. So, what types can you expect to encounter?

Textbooks

Probably the most familiar reading material in college is the textbook. These are academic books, usually focused on one discipline, and their primary purpose is to educate readers on a particular subject—”Principles of Algebra,” for example, or “Introduction to Business.” It’s not uncommon for instructors to use one textbook as the primary text for an entire course. Instructors typically assign chapters as readings and may include any word problems or questions in the textbook, too.

Articles

Instructors may also assign academic articles or news articles. Academic articles are written by people who specialize in a particular field or subject, while news articles may be from recent newspapers and magazines. For example, in a science class, you may be asked to read an academic article on the benefits of rainforest preservation, whereas in a government class, you may be asked to read an article summarizing a recent presidential debate. Instructors may have you read the articles online or they may distribute copies in class or electronically.

The chief difference between news and academic articles is the intended audience of the publication. News articles are mass media: They are written for a broad audience, and they are published in magazines and newspapers that are generally available for purchase at grocery stores or bookstores. They may also be available online. Academic articles, on the other hand, are usually published in scholarly journals with fairly small circulations. While you won’t be able to purchase individual journal issues from Barnes and Noble, public and school libraries do make these journal issues and individual articles available. It’s common to access academic articles through online databases hosted by libraries.

Literature and Nonfiction Books

Instructors use literature and nonfiction books in their classes to teach students about different genres, events, time periods, and perspectives. For example, a history instructor might ask you to read the diary of a girl who lived during the Great Depression so you can learn what life was like back then. In an English class, your instructor might assign a series of short stories written during the 1960s by different American authors, so you can compare styles and thematic concerns.

Literature includes short stories, novels or novellas, graphic novels, drama, and poetry. Nonfiction works include creative nonfiction—narrative stories told from real life—as well as history, biography, and reference materials. Textbooks and scholarly articles are specific types of nonfiction; often their purpose is to instruct, whereas other forms of nonfiction are written to inform, to persuade, or to entertain.

Purpose Of Academic Reading

Casual reading across genres, from books and magazines to newspapers and blogs, is something students should be encouraged to do in their free time because it can be both educational and fun. In college, however, instructors generally expect students to read resources that have particular value in the context of a course. Why is academic reading beneficial?

- Information comes from reputable sources: Web sites and blogs can be a source of insight and information, but not all are useful as academic resources. They may be written by people or companies whose main purpose is to share an opinion or sell you something. Academic sources such as textbooks and scholarly journal articles, on the other hand, are usually written by experts in the field and have to pass stringent peer review requirements in order to get published.

- Learn how to form arguments: In most college classes except for creative writing, when instructors ask you to write a paper, they expect it to be argumentative in style. This means that the goal of the paper is to research a topic and develop an argument about it using evidence and facts to support your position. Since many college reading assignments (especially journal articles) are written in a similar style, you’ll gain experience studying their strategies and learning to emulate them.

- Exposure to different viewpoints: One purpose of assigned academic readings is to give students exposure to different viewpoints and ideas. For example, in an ethics class, you might be asked to read a series of articles written by medical professionals and religious leaders who are pro-life or pro-choice and consider the validity of their arguments. Such experience can help you wrestle with ideas and beliefs in new ways and develop a better understanding of how others’ views differ from your own.

Active Learning When Reading

Many instructors conduct their classes mainly through lectures. The lecture remains the most pervasive teaching format across the field of higher education. One reason is that the lecture is an efficient way for the instructor to control the content, organization, and pace of a presentation, particularly in a large group. However, there are drawbacks to this “information-transfer” approach, where the instructor does all the talking and the students quietly listen: students have a hard time paying attention from start to finish; the mind wanders. Also, current cognitive science research shows that adult learners need an opportunity to practice newfound skills and newly introduced content. Lectures can set the stage for that interaction or practice, but lectures alone don’t foster student mastery. While instructors typically speak 100–200 words per minute, students hear only 50–100 of them. Moreover, studies show that students retain 70 percent of what they hear during the first ten minutes of class and only 20 percent of what they hear during the last ten minutes of class.

Thus it is especially important for students in lecture-based courses to engage in active learning outside of the classroom. But it’s also true for other kinds of college courses—including the ones that have active learning opportunities in class. Why? Because college students spend more time working (and learning) independently and less time in the classroom with the instructor and peers. Also, much of one’s coursework consists of reading and writing assignments. How can these learning activities be active? The following are very effective strategies to help you be more engaged with, and get more out of, the learning you do outside the classroom:

- Write in your books: You can underline and circle key terms, or write questions and comments in the margins of their books. The writing serves as a visual aid for studying and makes it easier for you to remember what you’ve read or what you’d like to discuss in class. If you are borrowing a book or want to keep it unmarked so you can resell it later, try writing keywords and notes on Post-its and sticking them on the relevant pages.

- Annotate a text: Annotations typically mean writing a brief summary of a text and recording the works-cited information (title, author, publisher, etc.). This is a great way to “digest” and evaluate the sources you’re collecting for a research paper, but it’s also invaluable for shorter assignments and texts since it requires you to actively think and write about what you read. The activity, below, will give you practice annotating texts.

- Create mind maps: Mind maps are effective visuals tools for students, as they highlight the main points of readings or lessons. Think of a mind map as an outline with more graphics than words. For example, if a student were reading an article about America’s First Ladies, she might write, “First Ladies” in a large circle in the center of a piece of paper. Connected to the middle circle would be lines or arrows leading to smaller circles with visual representations of the women discussed in the article. Then, these circles might branch out to even smaller circles containing the attributes of each of these women.

In addition to the strategies described above, the following are additional ways to engage in active reading and learning:

- Work when you are fully awake, and give yourself enough time to read a text more than once.

- Read with a pen or highlighter in hand, and underline or highlight significant ideas as you read.

- Interact with the ideas in the margins (summarize ideas; ask questions; paraphrase difficult sentences; make personal connections; answer questions asked earlier; challenge the author; etc.).

- As you read, keep the following in mind:

- What is the CONTEXT in which this text was written? (This writing contributes to what topic, discussion, or controversy? Context is bigger than this one written text.)

- Who is the intended AUDIENCE? (There’s often more than one intended audience.)

- What is the author’s PURPOSE? To entertain? To explain? To persuade? (There’s usually more than one purpose, and essays almost always have an element of persuasion.)

- How is this writing ORGANIZED? Compare and contrast? Classification? Chronological? Cause and effect? (There’s often more than one organizational form.)

- What is the author’s TONE? (What are the emotions behind the words? Are there places where the tone changes or shifts?)

- What TOOLS does the author use to accomplish her/his purpose? Facts and figures? Direct quotations? Fallacies in logic? Personal experience? Repetition? Sarcasm? Humor? Brevity?

- What is the author’s THESIS—the main argument or idea, condensed into one or two sentences?

- Foster an attitude of intellectual curiosity. You might not love all of the writing you’re asked to read and analyze, but you should have something interesting to say about it, even if that “something” is critical.

Reading Strategies For Academic Texts

Recall from the Active Learning section that effective reading requires more engagement than just reading the words on the page. In order to learn and retain what you read, it’s a good idea to do things like circling key words, writing notes, and reflecting. Actively reading academic texts can be challenging for students who are used to reading for entertainment alone, but practicing the following steps will get you up to speed.

SQ3R

SQ3R is a reading comprehension method named for its five steps: Survey, Question, Read, Recite, and Review. The method was introduced by Francis Pleasant Robinson, an American education philosopher in his 1946 book Effective Study.

The method offers an efficient and active approach to reading textbook material. It was created for college students but is extremely useful in a variety of situations. Classrooms all over the world have begun using this method to better understand what they’re reading.

Survey

You can gain insight from an academic text before you even begin the reading assignment. For example, if you are assigned a nonfiction book, read the title, the back of the book, and table of contents. Scanning this information can give you an initial idea of what you’ll be reading and some useful context for thinking about it. You can also start to make connections between the new reading and knowledge you already have, which is another strategy for retaining information. Survey the document by scanning its contents, gathering the necessary information to focus on topics and help set study goals.

- Read the title, introduction, summary or a chapter’s first paragraph(s). This helps to orient yourself to how this chapter is organized and to understand the topic’s key points.

- Go through each boldface heading and subheading. This will help you to create a mental structure for the topic.

- Check all graphics and captions closely. They’re there to emphasize certain points and provide rich additional information.

- Check reading aids and any footnotes. Emphasized text (italics, bold font, etc.) is typically introduced to catch the reader’s attention or to provide clarification.

Question

During this stage, you should note any questions on the subjects contained in the document. It is helpful to survey the textbook again, this time writing down the questions that you create while scanning each section. You can easily find what questions need to be answered by looking at the Learning Objectives at the beginning of a chapter, the headings, and sub-headings within the chapter and the Chapter Summary or Key Points at the end of a chapter. These questions become study goals and they will become information you’ll actively search later on while going through each section in detail.

- Write your questions down so you can fill in the answers as you read.

- Make sure to answer the questions in your own words, rather than copying directly from the text.

Read

Read each section thoroughly, keeping your questions in mind. Try to find the answers and identify if you need additional ones. Mind Mapping can probably help to make sense of and correlate all the information.

Recall/Recite

In the recall (or recite) stage, you should go through what you read and try to answer the questions you noted before. Check in after every section, chapter or topic to make sure you understand the material and can explain it, in your own words. It’s worth taking the time to write a short summary, even if your instructor doesn’t require it. The exercise of jotting down a few sentences or a short paragraph capturing the main ideas of the reading is enormously beneficial: it not only helps you understand and absorb what you read but gives you ready study and review materials for exams and other writing assignments. Pretend you are responsible for teaching this section to someone else. Can you do it? It’s at this stage that you consolidate knowledge, so refrain from moving on until you can recall the core information.

Review

Reviewing all the collected information is the final step of the process. In this stage, you can review the collected information, go through any particular chapter, expand your own notes, or discuss the topics with colleagues and other experts. An excellent way to consolidate information is to present or teach it to someone else. It always helps to revisit what you’ve read for a quick refresher. Before class discussions or tests, it’s a good idea to review your questions, summaries and any other notes you have taken.

Anatomy of a Textbook

Good textbooks are designed to help you learn, not just to present information. They differ from other types of academic publications intended to present research findings, advance new ideas, or deeply examine a specific subject. Textbooks have many features worth exploring because they can help you understand your reading better and learn more effectively. In your textbooks, look for the elements listed in the table below.

| Textbook Feature |

What It Is |

Why You Might Find It Helpful |

| Preface or Introduction |

A section at the beginning of a book in which the author or editor outlines its purpose and scope, acknowledges individuals who helped prepare the book, and perhaps outlines the features of the book. |

You will gain perspective on the author’s point of view, what the author considers important. If the preface is written with the student in mind, it will also give you guidance on how to “use” the textbook and its features. |

| Foreward |

A section at the beginning of the book, often written by an expert in the subject matter (different from the author) endorsing the author’s work and explaining why the work is significant. |

A foreword will give you an idea of what makes this book different from others in the field. It may provide hints as to why your instructor selected the book for your course. |

| Author Profile |

A short biography of the author illustrating the author’s credibility in the subject matter. |

This will help you understand the author’s perspective and what the author considers important. |

| Table of Contents |

A listing of all the chapters in the book and, in most cases, primary sections within chapters. |

The table of contents is an outline of the entire book. It will be very helpful in establishing links among the text, the course objectives, and the syllabus. |

| Chapter Preview or Learning Objectives |

A section at the beginning of each chapter in which the author outlines what will be covered in the chapter and what the student should expect to know or be able to do at the end of the chapter. |

These sections are invaluable for determining what you should pay special attention to. Be sure to compare these outcomes with the objectives stated in the course syllabus. |

| Introduction |

The first paragraph(s) of a chapter, which states the chapter’s objectives and key themes. An introduction is also common at the beginning of primary chapter sections. |

Introductions to chapters or sections are “must reads” because they give you a road map to the material you are about to read, pointing you to what is truly important in the chapter or section. |

| Applied Practice Elements |

Exercises, activities, or drills designed to let students apply their knowledge gained from the reading. Some of these features may be presented via Web sites designed to supplement the text. |

These features provide you with a great way to confirm your understanding of the material. If you have trouble with them, you should go back and reread the section. They also have the additional benefit of improving your recall of the material. |

| Chapter Summary |

A section at the end of a chapter that confirms key ideas presented in the chapter. |

It is a good idea to read this section before you read the body of the chapter. It will help you strategize about where you should invest your reading effort. |

| Review Material |

A section at the end of the chapter that includes additional applied practice exercises, review questions, and suggestions for further reading. |

The review questions will help you confirm your understanding of the material. |

| Endnotes and Bibliographies |

Formal citations of sources used to prepare the text. |

These will help you infer the author’s biases and are also valuable if doing further research on the subject for a paper. |

Strategies for Textbook Reading

The SQ3R system provides a proven approach to effective learning from texts. Following are some strategies you can use to enhance your reading even further:

- Pace yourself. Figure out how much time you have to complete the assignment. Divide the assignment into smaller blocks rather than trying to read the entire assignment in one sitting. If you have a week to do the assignment, for example, divide the work into five daily blocks, not seven; that way you won’t be behind if something comes up to prevent you from doing your work on a given day. If everything works out on schedule, you’ll end up with an extra day for review.

- Schedule your reading. Set aside blocks of time, preferably at the time of the day when you are most alert, to do your reading assignments. Don’t just leave them for the end of the day after completing written and other assignments.

- Get yourself in the right space. Choose to read in a quiet, well-lit space. Your chair should be comfortable but provide good support. Libraries were designed for reading—they should be your first option! Don’t use your bed for reading textbooks; since the time you were read bedtime stories, you have probably associated reading in bed with preparation for sleeping. The combination of the cozy bed, comforting memories, and dry text are sure to invite some shut-eye!

- Avoid distractions. Active reading takes place in your short-term memory. Every time you move from task to task, you have to “reboot” your short-term memory and you lose the continuity of active reading. Multitasking—listening to music or texting on your cell while you read—will cause you to lose your place and force you to start over again. Every time you lose focus, you cut your effectiveness and increase the amount of time you need to complete the assignment.

- Avoid reading fatigue. Work for about fifty minutes, and then give yourself a break for five to ten minutes. Put down the book, walk around, get a snack, stretch, or do some deep knee bends. Short physical activity will do wonders to help you feel refreshed.

- Read your most difficult assignments early in your reading time, when you are freshest.

- Make your reading interesting. Try connecting the material you are reading with your class lectures or with other chapters. Ask yourself where you disagree with the author. Approach finding answers to your questions like an investigative reporter. Carry on a mental conversation with the author.

- Highlight your reading material. Most readers tend to highlight too much, hiding key ideas in a sea of yellow lines, making it difficult to pick out the main points when it is time to review. When it comes to highlighting, less is more. Think critically before you highlight. Your choices will have a big impact on what you study and learn for the course. Make it your objective to highlight no more than 15-25% of what you read. Use highlighting after you have read a section to note the most important points, key terms, and concepts. You can’t know what the most important thing is unless you’ve read the whole section, so don’t highlight as you read.

- Annotate your reading material. Marking up your book may go against what you were told in high school when the school owned the books and expected to use them year after year. In college, you bought the book. Make it truly yours. Although some students may tell you that you can get more cash by selling a used book that is not marked up, this should not be a concern at this time—that’s not nearly as important as understanding the reading and doing well in the class! The purpose of marking your textbook is to make it your personal studying assistant with the key ideas called out in the text. Use your pencil also to make annotations in the margin. Use a symbol like an exclamation mark (!) or an asterisk (*) to mark an idea that is particularly important. Use a question mark (?) to indicate something you don’t understand or are unclear about. Box new words, then write a short definition in the margin. Use “TQ” (for “test question”) or some other shorthand or symbol to signal key things that may appear in test or quiz questions. Write personal notes on items where you disagree with the author. Don’t feel you have to use the symbols listed here; create your own if you want, but be consistent. Your notes won’t help you if the first question you later have is “I wonder what I meant by that?”

- Get to Know the Conventions. Academic texts, like scientific studies and journal articles, may have sections that are new to you. If you’re not sure what an “abstract” is, research it online or ask your instructor. Understanding the meaning and purpose of such conventions is not only helpful for reading comprehension but for writing, too.

- Look up and Keep Track of Unfamiliar Terms and Phrases. Have a good college dictionary such as Merriam-Webster handy (or find it online) when you read complex academic texts, so you can look up the meaning of unfamiliar words and terms. Many textbooks also contain glossaries or “key terms” sections at the ends of chapters or the end of the book. If you can’t find the words you’re looking for in a standard dictionary, you may need one specially written for a particular discipline. For example, a medical dictionary would be a good resource for a course in anatomy and physiology. If you circle or underline terms and phrases that appear repeatedly, you’ll have a visual reminder to review and learn them. Repetition helps to lock in these new words and their meaning get them into long-term memory, so the more you review them the more you’ll understand and feel comfortable using them.

- Make Flashcards. If you are studying certain words for a test, or you know that certain phrases will be used frequently in a course or field, try making flashcards for review. For each key term, write the word on one side of an index card and the definition on the other. Drill yourself, and then ask your friends to help quiz you. Developing a strong vocabulary is similar to most hobbies and activities. Even experts in a field continue to encounter and adopt new words. The following video discusses more strategies for improving vocabulary.

Dealing With Special Texts

While the active reading process outlined earlier is very useful for most assignments, you should consider some additional strategies for reading assignments in other subjects.

Mathematics Texts

Mathematics presents unique challenges in that they typically contain a great number of formulas, charts, sample problems, and exercises. Follow these guidelines:

- Do not skip over these special elements as you work through the text.

- Read the formulas and make sure you understand the meaning of all the factors.

- Substitute actual numbers for the variables and work through the formula.

- Make formulas real by applying them to real-life situations.

- Do all exercises within the assigned text to make sure you understand the material.

- Since mathematical learning builds upon prior knowledge, do not go on to the next section until you have mastered the material in the current section.

- Seek help from the instructor or teaching assistant during office hours if need be.

Scientific Texts

Science occurs through the experimental process: posing hypotheses, and then using experimental data to prove or disprove them. When reading scientific texts, look for hypotheses and list them in the left column of your notes pages. Then make notes on the proof (or disproof) in the right column. In scientific studies, these are as important as the questions you ask for other texts. Think critically about the hypotheses and the experiments used to prove or disprove them. Think about questions like these:

- Can the experiment or observation be repeated? Would it reach the same results?

- Why did these results occur? What kinds of changes would affect the results?

- How could you change the experiment design or method of observation? How would you measure your results?

- What are the conclusions reached about the results? Could the same results be interpreted in a different way?

Social Sciences Texts

Social sciences texts, such as those for history, economics, and political science classes, often involve interpretation where the authors’ points of view and theories are as important as the facts they present. Put your critical thinking skills into overdrive when you are reading these texts. As you read, ask yourself questions such as the following:

- Why is the author using this argument?

- Is it consistent with what we’re learning in class?

- Do I agree with this argument?

- Would someone with a different point of view dispute this argument?

- What key ideas would be used to support a counterargument?

Record your reflections in the margins and in your notes.

Social science courses often require you to read primary source documents. Primary sources include documents, letters, diaries, newspaper reports, financial reports, lab reports, and records that provide firsthand accounts of the events, practices, or conditions you are studying. Start by understanding the author(s) of the document and his or her agenda. Infer their intended audience. What response did the authors hope to get from their audience? Do you consider this a bias? How does that bias affect your thinking about the subject? Do you recognize personal biases that affect how you might interpret the document?

Foreign Language Texts

Reading texts in a foreign language is particularly challenging, but it also provides you with invaluable practice and many new vocabulary words in your “new” language. It is an effort that really pays off. Start by analyzing a short portion of the text (a sentence or two) to see what you do know. Remember that all languages are built on idioms as much as on individual words. Do any of the phrase structures look familiar? Can you infer the meaning of the sentences? Do they make sense based on the context? If you still can’t make out the meaning, choose one or two words to look up in your dictionary and try again. Look for longer words, which generally are the nouns and verbs that will give you meaning sooner. Don’t rely on a dictionary (or an online translator); a word-for-word translation does not always yield good results. For example, the Spanish phrase “Entre y tome asiento” might correctly be translated (word for word) as “Between and drink a seat,” which means nothing, rather than its actual meaning, “Come in and take a seat.”

Reading in a foreign language is hard and tiring work. Make sure you schedule significantly more time than you would normally allocate for reading in your own language and reward yourself with more frequent breaks. But don’t shy away from doing this work; the best way to learn a new language is practice, practice, practice.

Note to English-language learners: You may feel that every book you are assigned is in a foreign language. If you do struggle with the high reading level required of college students, check for college resources that may be available to ESL (English as a second language) learners. Never feel that those resources are only for weak students. As a second-language learner, you possess a rich linguistic experience that many American-born students should envy. You simply need to account for the difficulties you’ll face and (like anyone learning a new language) practice, practice, practice.

Reading Graphics

You read earlier about noticing graphics in your text as a signal of important ideas. But it is equally important to understand what the graphics intend to convey. Textbooks contain tables, charts, maps, diagrams, illustrations, photographs, and the newest form of graphics, Internet URLs for accessing text and media material. Many students are tempted to skip over the graphic material and focus only on the reading. Don’t! Take the time to read and understand your textbook’s graphics. They will increase your understanding, and because they engage different comprehension processes, they will create different kinds of memory links to help you remember the material.

To get the most out of graphic material, use your critical thinking skills and question why each illustration is present and what it means. Don’t just glance at the graphics; take the time to read the title, caption, and any labeling in the illustration. In a chart, read the data labels to understand what is being shown or compared. Think about projecting the data points beyond the scope of the chart; what would happen next? Why?

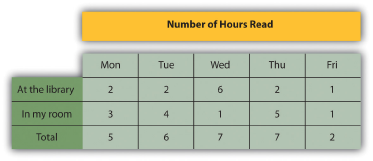

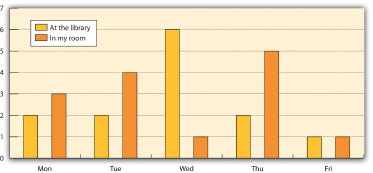

The table below shows the most common graphic elements and notes what they do best. This knowledge may help guide your critical analysis of graphic elements.

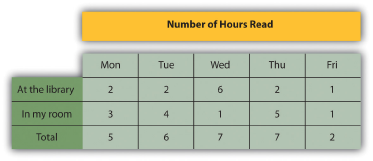

|

TABLE

Most often used to present raw data. Understand what is being measured. What data points stand out as very high or low?Why? Ask yourself what might cause these measurements to change.

|

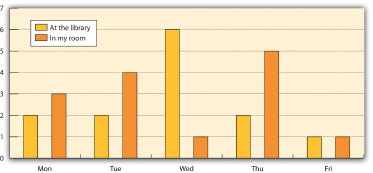

|

BAR CHART

Used to compare quantitative data or show changes in data over time. Also can be used to compare a limited number of data series over time. Often an illustration of data that can also be presented in a table.

|

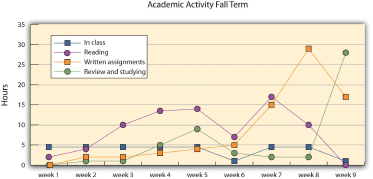

|

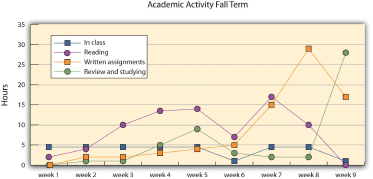

LINE CHART

Used to illustrate a trend in a series of data. May be used to compare different series over time.

|

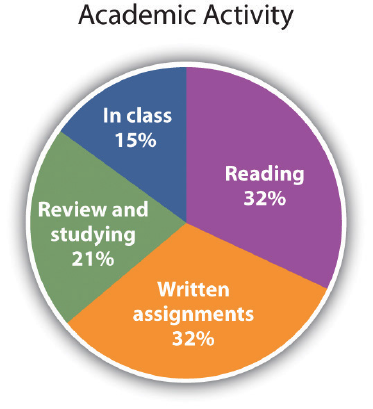

|

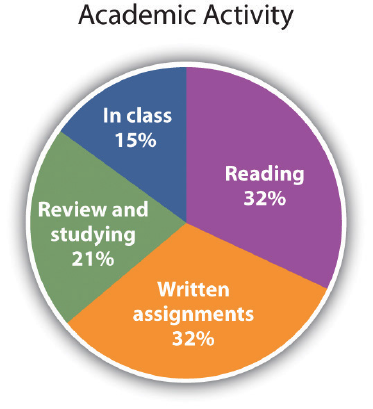

PIE CHART

Used to illustrate the distribution or share of elements as a part of a whole. Ask yourself what effect a change in the distribution of factors would have on the whole.

|

|

MAP

Used to illustrate geographic distributions or movement across geographical space. In some cases can be used to show concentrations of populations or resources. When encountering a map, ask yourself if changes or comparisons are being illustrated. Understand how those changes or comparisons relate to the material in the text.

|

|

PHOTO

Used to represent a person, a condition, or an idea discussed in the text. Sometimes photographs serve mainly to emphasize an important person or situation, but photographs can also be used to make a point. Ask yourself if the photograph reveals a biased point of view.

|

|

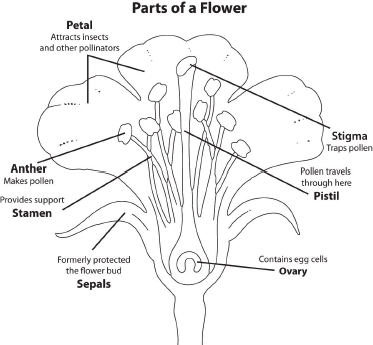

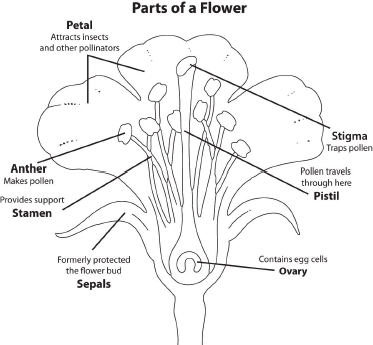

ILLUSTRATION

Used to illustrate parts of an item. Invest time in these graphics. They are often used as parts of quizzes or exams. Look carefully at the labels. These are vocabulary words you should be able to define.

|

|

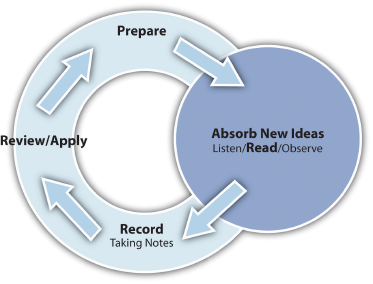

FLOWCHART or DIAGRAM

Commonly used to illustrate processes. As you look at diagrams, ask yourself, “What happens first? What needs to happen to move to the next step?”

|

Online Texts

Reading online texts presents unique challenges for some students. For one thing, you can’t readily circle or underline key terms or passages on the screen with a pencil. For another, there can be many tempting distractions while reading online – just a quick visit to social media sites or to check your email.

While there’s no substitute for old-fashioned self-discipline, you can take advantage of the following tips to make online reading more efficient and effective:

- Get a browser extension that allows you to highlight and annotate your online text.

- If possible, download the reading as a PDF, Word document, etc., so you can read it offline.

- Get an app or browser extension that disables your social media sites for specified periods of time.

- Adjust your screen to avoid glare and eye strain, and change the text font to be less distracting (for those essays written in Comic Sans).

- Follow the SQ3R system, taking notes and answering questions as you go. Since highlighting and annotating are more difficult with online texts, it is imperative that you take quality notes.

- Look for reputable online sources. Professors tend to assign reading from reputable print and online sources, so you can feel comfortable referencing such sources in class and for writing assignments. If you are looking for online sources independently, however, devote some time and energy to critically evaluating the quality of the source before spending time reading any resources you find there. Find out what you can about the author (if one is listed), the Website, and any affiliated sponsors it may have. Check that the information is current and accurate against similar information on other pages. Depending on what you are researching, sites that end in “.edu” (indicating an “education” site such as a college, university, or other academic institution) tend to be more reliable than “.com” sites. Check with a librarian for help in identifying reputable online sources.

Building Your Vocabulary

Gaining confidence with the unique terminology used in different disciplines can help you be more successful in your courses and in college generally. A good vocabulary is essential for success in any role that involves communication, and just about every role in life requires good communication skills. We include this section on vocabulary in this chapter on reading because of the connections between vocabulary building and reading. Building your vocabulary will make your reading easier, and reading is the best way to build your vocabulary.

Learning new words can be fun and does not need to involve tedious rote memorization of word lists. The first step, as with any other aspect of the learning cycle, is to prepare yourself to learn. Consciously decide that you want to improve your vocabulary; decide you want to be a student of words. Work to become more aware of the words around you: the words you hear, the words you read, the words you say, and those you write.

In addition to the suggestions described earlier, such as looking up unfamiliar words in dictionaries, the following are additional vocabulary-building techniques for you to try:

- Read everything and read often. Reading frequently both in and out of the classroom will help strengthen your vocabulary. Whenever you read a book, magazine, newspaper, blog, or any other resource, keep a running list of words you don’t know. Look up the words as you encounter them and try to incorporate them into your own speaking and writing.

- Be on the lookout for new words. Most will come to you as you read, but they may also appear in an instructor’s lecture, a class discussion, or a casual conversation with a friend. They may pop up in random places like billboards, menus, or even online ads!

- Write down the new words you encounter, along with the sentences in which they were used. Do this in your notes with new words from a class or reading assignment. If a new word does not come from a class, you can write it on just about anything, but make sure you write it. Many word lovers carry a small notepad or a stack of index cards specifically for this purpose.

- Infer the meaning of the word. The context in which the word is used may give you a good clue about its meaning. Do you recognize a common word root in the word? What do you think it means?

- Look up the word in a dictionary. Do this as soon as possible (but only after inferring the meaning). When you are reading, you should have a dictionary at hand for this purpose. In other situations, do this within a couple hours, definitely during the same day. How does the dictionary definition compare with what you inferred? Install a reliable dictionary app on your phone or computer. Look for ones that also pronounce the word.

- Make connections to words you already know. You may be familiar with the “looks like . . . sounds like” saying that applies to words. It means that you can sometimes look at a new word and guess the definition based on similar words whose meaning you know. For example, if you are reading a biology book on the human body and come across the word malignant, you might guess that this word means something negative or broken if you already know the word malfunction, which shares the “mal-” prefix.

- Write the word in a sentence, ideally one that is relevant to you. If the word has more than one definition, write a sentence for each.

- Say the word out loud and then say the definition and the sentence you wrote.

- Use the word. Find an occasion to use the word in speech or writing over the next two days.

- Schedule a weekly review with yourself to go over your new words and their meaning.

Key Takeaways

- College reading is very different from high school reading.

- You must take personal responsibility for understanding what you read.

- Expect to spend about two or more hours on homework, most of it reading, for every hour you spend in class.

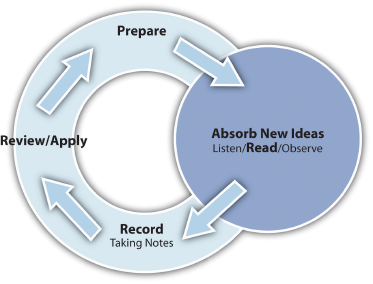

- Reading is a primary means for absorbing ideas in the learning cycle, but it is also very important for the other three aspects of the learning cycle.

- Understand how your textbook is put together and what features might help you with your reading.

- Plan your reading by scanning the reading assignment first, then create questions based on the section titles. Use the SQ3R system to help you focus and prioritize your reading.

- Don’t try to highlight your text as you read the first time through. At that point, it is hard to tell what is really important. Aim to highlight 15-25% of the text.

- End your reading time by reviewing your notes.

- Do all the exercises in math textbooks; apply the formulas to real-world situations.

- Each type of graphic material has its own strength; those strengths are usually clues about what the author wants to emphasize by using the graphic.

- Look for statements of hypotheses and experimental design when reading science texts.

- History, economics, and political science texts are heavily influenced by interpretation. Think critically about what you are reading.

- Working with foreign language texts requires more time and more frequent breaks. Don’t rely on word-for-word translations.

- The best way to build your vocabulary is to read, and a stronger vocabulary makes it easier and more fun to read.

- Look for new words everywhere, not just in class readings.

- Look up new words in the dictionary, write your own sentence using the new word. Say the word and definition out loud. Use the new word as soon as possible.

Authored by: Heather Syrett. Provided by: Austin Community College.

License: CC Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)