Students don’t always want to go to class. They may have required classes that they find difficult or don’t enjoy, or they may feel overwhelmed by other commitments or feel tired if they have early morning classes. However, even if instructors allow a certain number of unexcused absences, you should aim to attend every class session. Class attendance enhances class performance in the following ways:

Let’s compare students with different attitudes toward their classes:

Carla wants to get through college, and she knows she needs the degree to get a decent job, but she’s just not that into it. She’s never thought of herself as a good student, and that hasn’t changed much in college. She has trouble paying attention in those big lecture classes, which mostly seem pretty boring. She’s pretty sure she can pass all her courses, however, as long as she takes the time to study before tests. It doesn’t bother her to skip classes when she’s studying for a test in a different class or finishing a reading assignment she didn’t get around to earlier. She does make it through her freshman year with a passing grade in every class, even those she didn’t go to very often. Then she fails the midterm exam in her first sophomore class. Depressed, she skips the next couple classes, then feels guilty and goes to the next. It’s even harder to stay awake because now she has no idea what they’re talking about. It’s too late to drop the course, and even a hard night of studying before the final isn’t enough to pass the course. In two other classes, she just barely passes. She has no idea what classes to take next term and is starting to think that maybe she’ll drop out for now.

Karen wants to have a good time in college and still do well enough to get a good job in business afterward. Her sorority keeps a file of class notes for her big lecture classes, and from talking to others and reviewing these notes, she’s discovered she can skip almost half of those big classes and still get a B or C on the tests. She stays focused on her grades, and because she has a good memory, she’s able to maintain OK grades. She doesn’t worry about talking to her instructors outside of class because she can always find out what she needs from another student. In her sophomore year, she has a quick conversation with her academic advisor and chooses her major. Those classes are smaller, and she goes to most of them, but she feels she’s pretty much figured out how it works and can usually still get the grade. In her senior year, she starts working on her résumé and asks other students in her major which instructors write the best letters of recommendation. She’s sure her college degree will land her a good job.

Alicia enjoys her classes, even when she has to get up early after working or studying late the night before. She sometimes gets so excited by something she learns in class that she rushes up to the instructor after class to ask a question. In class discussions, she’s not usually the first to speak out, but by the time another student has given an opinion, she’s had time to organize her thoughts and enjoys arguing her ideas. Nearing the end of her sophomore year and unsure of what to major in given her many interests, she talks things over with one of her favorite instructors, whom she has gotten to know through office visits. The instructor gives her some insights into careers in that field and helps her explore her interests. She takes two more courses with this instructor over the next year, and she’s comfortable in her senior year going to him to ask for a job reference. When she does, she’s surprised and thrilled when he urges her to apply for a high-level paid internship with a company in the field—that happens to be run by a friend of his.

Think about the differences in the attitudes of these three students and how they approach their classes. One’s attitude toward learning, toward going to class, and toward the whole college experience is a huge factor in how successful a student will be. Make it your goal to attend every class; don’t even think about not going. Going to class is the first step in engaging in your education by interacting with the instructor and other students. Here are some reasons why it’s important to attend every class:

Listening is a skill of critical significance in all aspects of our lives, from maintaining our personal relationships, to getting our jobs done, to taking notes in class, to figuring out which bus to take to the airport. Regardless of how we’re engaged with listening, it’s important to understand that listening involves more than just hearing the words that are directed at us. Listening is an active process by which we make sense of, assess, and respond to what we hear.

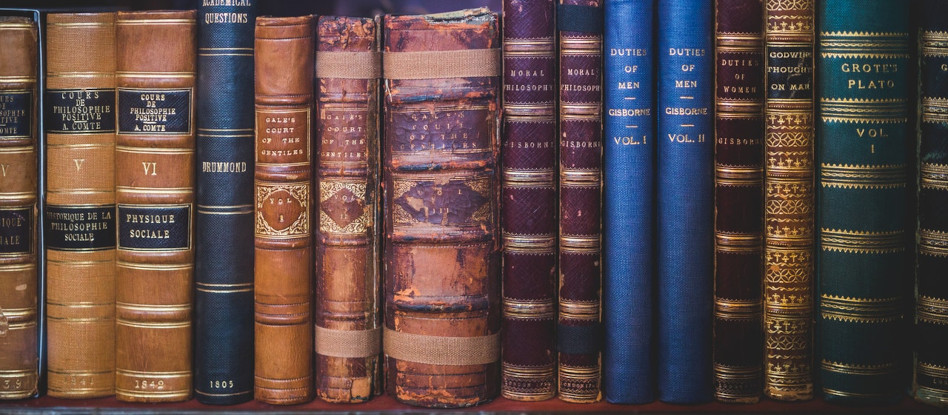

The listening process involves five stages: receiving, understanding, evaluating, remembering, and responding. These stages will be discussed in more detail in later sections. An effective listener must hear and identify the speech sounds directed toward them, understand the message of those sounds, critically evaluate or assess that message, remember what’s been said, and respond (either verbally or nonverbally) to information they’ve received.

Effectively engaging in all five stages of the listening process lets us best gather the information we need from the world around us.

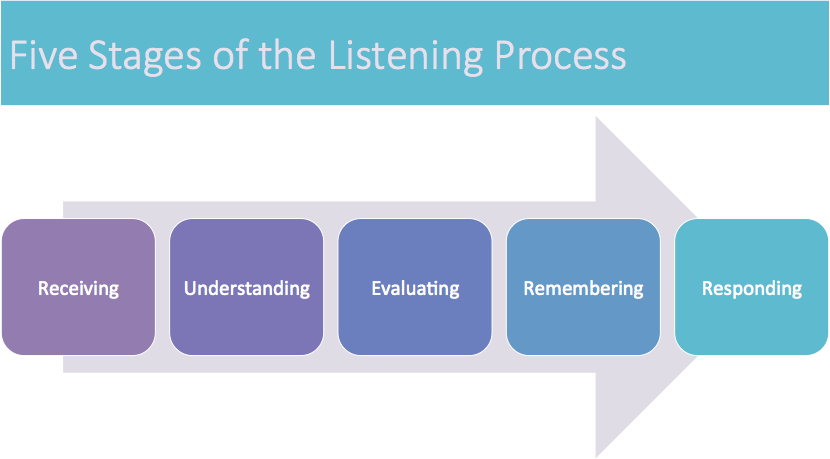

Active listening is a particular communication technique that requires the listener to provide feedback on what he or she hears to the speaker, by way of restating or paraphrasing what they have heard in their own words. The goal of this repetition is to confirm what the listener has heard and to confirm the understanding of both parties. The ability to actively listen demonstrates sincerity, and that nothing is being assumed or taken for granted. Active listening is most often used to improve personal relationships, reduce misunderstanding and conflicts, strengthen cooperation, and foster understanding.

When engaging with a particular speaker, a listener can use several degrees of active listening, each resulting in a different quality of communication with the speaker. This active listening chart shows three main degrees of listening: repeating, paraphrasing, and reflecting.

Active listening can also involve paying attention to the speaker’s behavior and body language. Having the ability to interpret a person’s body language lets the listener develop a more accurate understanding of the speaker’s message.

The first stage of the listening process is the receiving stage, which involves hearing and attending.

Hearing is the physiological process of registering sound waves as they hit the eardrum. As obvious as it may seem, in order to effectively gather information through listening, we must first be able to physically hear what we’re listening to. The clearer the sound, the easier the listening process becomes.

Paired with hearing, attending is the other half of the receiving stage in the listening process. Attending is the process of accurately identifying and interpreting particular sounds we hear as words. The sounds we hear have no meaning until we give them their meaning in context. Listening is an active process that constructs meaning from both verbal and nonverbal messages.

Attending also involves being able to discern human speech, also known as “speech segmentation. “1 Identifying auditory stimuli as speech but not being able to break those speech sounds down into sentences and words would be a failure of the listening process. Discerning speech segmentation can be a more difficult activity when the listener is faced with an unfamiliar language.

The second stage in the listening process is the understanding stage. Understanding or comprehension is “shared meaning between parties in a communication transaction” and constitutes the first step in the listening process. This is the stage during which the listener determines the context and meanings of the words he or she hears. Determining the context and meaning of individual words, as well as assigning meaning in language, is essential to understanding sentences. This, in turn, is essential to understanding a speaker’s message.

Once the listener understands the speaker’s main point, they can begin to sort out the rest of the information they are hearing and decide where it belongs in their mental outline. For example, a political candidate listens to her opponent’s arguments to understand what policy decisions that opponent supports.

Before getting the big picture of a message, it can be difficult to focus on what the speaker is saying. Think about walking into a lecture class halfway through. You may immediately understand the words and sentences that you are hearing, but not immediately understand what the lecturer is proving or whether what you’re hearing at the moment is the main point, side note, or digression.

Understanding what we hear is a huge part of our everyday lives, particularly in terms of gathering basic information. In the office, people listen to their superiors for instructions about what they are to do. At school, students listen to teachers to learn new ideas. We listen to political candidates give policy speeches in order to determine who will get our vote. But without understanding what we hear, none of this everyday listening would relay any practical information to us.

One tactic for better understanding a speaker’s meaning is to ask questions. Asking questions allows the listener to fill in any holes he or she may have in the mental reconstruction of the speaker’s message.

This stage of the listening process is the one during which the listener assesses the information they received, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Evaluating allows the listener to form an opinion of what they heard and, if necessary, to begin developing a response.

During the evaluating stage, the listener determines whether or not the information they heard and understood from the speaker is well constructed or disorganized, biased or unbiased, true or false, significant or insignificant. They also ascertain how and why the speaker has come up with and conveyed the message that they delivered. This may involve considerations of a speaker’s personal or professional motivations and goals. For example, a listener may determine that a co-worker’s vehement condemnation of another for jamming the copier is factually correct, but may also understand that the co-worker’s child is sick and that may be putting them on edge. A voter who listens to and understands the points made in a political candidate’s stump speech can decide whether or not those points were convincing enough to earn their vote.

The evaluating stage occurs most effectively once the listener fully understands what the speaker is trying to say. While we can, and sometimes do, form opinions of information and ideas that we don’t fully understand—or even that we misunderstand—doing so is not often ideal in the long run. Having a clear understanding of a speaker’s message allows a listener to evaluate that message without getting bogged down in ambiguities or spending unnecessary time and energy addressing points that may be tangential or otherwise non-essential.

This stage of critical analysis is important for a listener in terms of how what they heard will affect their own ideas, decisions, actions, and/or beliefs.

In the listening process, the remembering stage occurs as the listener categorizes and retains the information she’s gathered from the speaker for future access. The result–memory–allows the person to record information about people, objects, and events for later recall. This happens both during and after the speaker’s delivery.

Memory is essential throughout the listening process. We depend on our memory to fill in the blanks when we’re listening and to let us place what we’re hearing at the moment in the context of what we’ve heard before. If, for example, you forgot everything that you heard immediately after you heard it, you would not be able to follow along with what a speaker says, and conversations would be impossible. Moreover, a friend who expresses fear about a dog she sees on the sidewalk ahead can help you recall that the friend began the conversation with her childhood memory of being attacked by a dog.

Remembering previous information is critical to moving forward. Similarly, making associations to past remembered information can help a listener understand what she is currently hearing in a wider context. In listening to a lecture about the symptoms of depression, for example, a listener might make a connection to the description of a character in a novel that she read years before.

Using information immediately after receiving it enhances information retention and lessens the forgetting curve or the rate at which we no longer retain information in our memory. Conversely, retention is lessened when we engage in mindless listening, and little effort is made to understand a speaker’s message.

Because everyone has different memories, the speaker and the listener may attach different meanings to the same statement. In this sense, establishing common ground in terms of context is extremely important, both for listeners and speakers.

The responding stage is the stage of the listening process wherein the listener provides verbal and/or nonverbal reactions based on short- or long-term memory. Following the remembering stage, a listener can respond to what they hear either verbally or non-verbally. Nonverbal signals can include gestures such as nodding, making eye contact, tapping a pen, fidgeting, scratching or cocking their head, smiling, rolling their eyes, grimacing, or any other body language. These kinds of responses can be displayed purposefully or involuntarily. Responding verbally might involve asking a question, requesting additional information, redirecting or changing the focus of a conversation, cutting off a speaker, or repeating what a speaker has said back to her in order to verify that the received message matches the intended message.

Nonverbal responses like nodding or eye contact allow the listener to communicate their level of interest without interrupting the speaker, thereby preserving the speaker/listener roles. When a listener responds verbally to what they hear and remember—for example, with a question or a comment—the speaker/listener roles are reversed, at least momentarily.

Responding adds action to the listening process, which would otherwise be an outwardly passive process. Oftentimes, the speaker looks for verbal and nonverbal responses from the listener to determine if and how their message is being understood and/or considered. Based on the listener’s responses, the speaker can choose to either adjust or continue with the delivery of her message. For example, if a listener’s brow is furrowed and their arms are crossed, the speaker may determine that she needs to lighten their tone to better communicate their point. If a listener is smiling and nodding or asking questions, the speaker may feel that the listener is engaged and her message is being communicated effectively.

Too many students try to get the grade just by going to class, maybe a little note taking, and then cramming through the text right before an exam they feel unprepared for. Sound familiar? This approach may have worked for you in high school where tests and quizzes were more frequent and teachers prepared study guides for you, but colleges require you to take responsibility for your learning and to be better prepared.

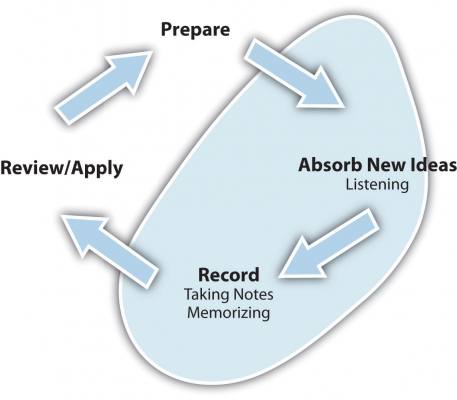

Most students simply have not learned how to study and don’t understand how learning works. Learning is actually a cycle of four steps:

When you get in the habit of paying attention to this cycle, it becomes relatively easy to study well. But you must use all four steps.

This chapter focuses on listening, a key skill for learning new material. The next chapter focuses on note-taking, the most important skill in the capturing phase of the cycle. These skills are closely related. Good listening skills make you a better note taker, and taking good notes can help you listen better. Both are key study skills to help you do better in your classes.

Are you a good listener? Most of us like to think we are, but when we really think about it, we recognize that we are often only half listening. We’re distracted, thinking about other things, or formulating what we are going to say in reaction to what we are hearing before the speaker has even finished. Effective listening is one of the most important learning tools you can have in college. And it is a skill that will benefit you on the job and help your relationships with others. Listening is nothing more than purposefully focusing on what a speaker is saying with the objective of understanding.

This definition is straightforward, but there are some important concepts that deserve a closer look. “Purposefully focusing” implies that you are actively processing what the speaker is saying, not just letting the sounds of their voice register in your senses. “With the objective of understanding” means that you will learn enough about what the speaker is saying to be able to form your own thoughts about the speaker’s message. Listening is an active process, as opposed to hearing, which is passive.

You listen to others in many situations: to interact with friends, to get instructions for a task, or to learn new material. There are two general types of listening situations: where you will be able to interact freely with the speaker (everyday conversations, small discussion classes, business meetings) and where interaction is limited (lectures and Webcasts).

In interactive situations, you should apply the basic principles of active listening. These are not hard to understand, but they are hard to implement and require practice to use them effectively.

Listening in a classroom or lecture hall to learn can be challenging because you are limited by how, and how much, you can interact with an instructor during the class. The following strategies help make listening at lectures more effective and learning more fun.

Are you shy about asking questions? Do you think that others in the class will ridicule you for asking a dumb question? Students sometimes feel this way because they have never been taught how to ask questions. Practice these steps, and soon you will be on your way to customizing each course to meet your needs and letting the instructor know you value the course.

Like listening, participating in class will help you get more out of class. It may also help you stand out as a student. Instructors notice the students who participate in class (and those who don’t), and participation is often a component of the final grade. “Participation” may include contributing to discussions, class activities, or projects. It means being actively involved. The following are some strategies for effective participation:

Smaller classes generally favor discussion, but often instructors in large lecture classes also make some room for participation.

A concern or fear about speaking in public is one of the most common fears. If you feel afraid to speak out in class, take comfort from the fact that many others do as well—and that anyone can learn how to speak in class without much difficulty. Class participation is actually an impromptu, informal type of public speaking, and the same principles will get you through both: preparing and communicating.

Being prepared is especially important in lecture classes. Have assigned readings done before class and review your notes. If you have a genuine question about something in the reading, ask about it. Jot down the question in your notes and be ready to ask if the lecture doesn’t clear it up for you.

Being prepared before asking a question also includes listening carefully to the lecture. You don’t want to ask a question whose answer was already given by the instructor in the lecture. Take a moment to organize your thoughts and choose your words carefully. Be as specific as you can. Don’t say something like, “I don’t understand the big deal about whether the earth revolves around the sun or the sun around the earth. So what?” Instead, you might ask, “When they discovered that the earth revolves around the sun, was that such a disturbing idea because people were upset to realize that maybe they weren’t the center of the universe?” The first question suggests you haven’t thought much about the topic, while the second shows that you are beginning to grasp the issue and want to understand it more fully.

Following are some additional guidelines for asking good questions:

A note on technology in the lecture hall. Colleges are increasingly incorporating new technology in lecture halls. For example, each student in the lecture hall may have an electronic “clicker” with which the instructor can gain instant feedback on questions in class. Or the classroom may have wireless Internet and students are encouraged to use their laptops to communicate with the instructor in “real time” during the lecture. In these cases, the most important thing is to take it seriously, even if you have anonymity. Most students appreciate the ability to give feedback and ask questions through such technology, but some abuse their anonymity by sending irrelevant, disruptive, or insulting messages.

As you learned in Unit 3, students have many different learning preferences and intelligences. Understanding your stengths and preferences can help you study more effectively. Most instructors tend to develop their own teaching style, however, and you will encounter different teaching styles in different courses. Students can benefit from having instructors who teach in different ways because it can help them become more versatile as learners and able to work and communicate with a variety of people. Variety can be a challenge for students who prefer to learn in specific settings. However, learning to recognize different teaching styles can help students adjust to them and still be successful. Below are descriptions of some main teaching styles and how they relate to different learning preferences:

When the instructor’s teaching style matches your learning preferences, you are usually more attentive in class and may seem to learn better. But what happens if your instructor has a style very different from your own? Let’s say, for example, that your instructor primarily lectures, speaks rapidly, and seldom uses visuals. This instructor also talks mostly on the level of large abstract ideas and almost never gives examples. Let’s say that you, in contrast, prefer more visual demonstrations, that you prefer visual aids and visualizing concrete examples of ideas. Therefore, perhaps you are having some difficulty paying attention in class and following the lectures. What can you do?

Megan is currently taking two classes: geology and American literature. In her geology class, the instructor lectures for the full class time and gives reading assignments. In Megan’s literature class, however, the instructor relies on class discussions, small group discussions, and occasionally even review games. Megan enjoys her literature class, but she struggles to feel engaged and interested in geology.What strategies can Megan use to stay motivated and involved in both of her courses?

Think about the college classes you’ve taken so far. Like Megan, you may feel like it’s a mixed bag: you probably enjoyed the courses with a variety of teaching styles and learning activities the most. Even if you’re a quieter, more reserved student who dislikes lots of group discussions, you probably prefer to have some class projects or writing assignments rather than lectures alone. Group projects, discussions, and writing are examples of active learning because they involve doing something. Active learning happens when students participate in their education through activities that enhance learning. Those activities may involve just thinking about what you’re learning. Active learning can take place both in and out of the classroom. The following are examples of activities that can facilitate active engagement in the classroom.

Class discussions: Class discussions can help students stay focused because they feature different voices besides that of the instructor. Students can also hear one another’s questions and comments and learn from one another. Such discussions may involve the entire class, or the instructor may organize smaller groups, giving quieter students a greater chance to talk. Another method is to create online discussion boards so that students have more time to develop their ideas and comments and keep the conversation going.

Writing assignments: Instructors may ask students to write short reaction papers or journal entries about lessons or reading assignments. Such assignments can help students review or reflect on what they just learned to help them understand and remember the material, and also provide a means of communicating questions and concerns to their instructors.

Student-led teaching: Many instructors believe that a true test of whether students understand concepts is being able to teach the material to others. For that reason, instructors will sometimes have students work in groups and research a topic or review assigned readings, and then prepare a mini-presentation and teach it to the rest of the class. This activity can help students feel more accountable for their learning and work harder since classmates will be relying on them.

Authored by: Heather Syrett. Provided by: Austin Community College.

License: CC Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)